This section provides further information and examples on:

- To give effect to

- The permitted baseline

- Possible plan numbering system

- Cascade approaches

- Ideas for providing certainty in plan rules

- Cross-references in RMA plans

- Ideas for the use of plain English in plans

- Promoting internal consistency in RMA plans

- Testing issues for RMA plans

- Zoning as a tool in plans

- The planning process cycle under the RMA

- Example issues

- Example plan issues, objectives and policies

- Example District Plan rules

- Example Regional Plan rules

- Examples of definition styles

'..Give effect to... ' a discussion

Sections 67(3) and 75(3) require that plans 'must give effect to' national and regional policy statements.

This requirement for plans to 'give effect' to regional policy statements is designed to give regional policy statements more influence over local policy. It is important that local policy reflects the priorities of the region and is proactive in helping support the integrated management of natural and physical resources of the whole region. Similarly, the requirement to give effect to national policy statements ensures a nationally consistent approach on relevant issues.

Sections 67 and 75 essentially codify case law that said district plans needed to give effect to (or implement) regional policy statements if those policy statements were framed in a directive way.

A possible meaning of 'give effect to'

The RMA does not provide any direct guidance as to meaning or requirements of what 'give effect to' is intended to mean and there is an absence of case law to test the exact meaning. However, the following discussion offers thoughts and suggestions based on reports and similar wording contained in law and case law.

The words 'give effect to' are intended to convey that plans should actively implement the regional policy statement (the policies, the methods, or both, as applicable)

In determining if a plan that is being prepared 'gives effect to' a regional policy statement, check to include:

- what parts of the national or regional policy statement have direct relevance to the plan (are there similarities in topics covered, issues, or objectives and policies that relate to the same area that is covered by the plan?)

- whether the national or regional policy statement contains specific sections, formatting or wording that shows the objectives, policies, or methods that must be given effect to through the plan

- to see if the national or regional policy statement expresses objectives and policies in a way that suggests that their implementation is mandatory (for instance using words like 'shall' , 'all councils must')

- if the plan being prepared reflects the mandatory provisions contained in the national or regional policy statement (through expressing the same or similar wording or intent in objectives, policies or both)

- if the plan being prepared contains rules, or provides a recognisable framework for other methods that implement the objectives and policies of the regional policy statement.

Possible implications of 'give effect to'

- National policy statements need to contain clear wording which identifies the specific objectives and policies that are to be included in plans.

- Provisions in the regional policy statement that are to be given effect to, need to be worded in a substantially more directive manner than in the first generation of regional policy statements. For example:

"District Plans will include provisions for the setting aside of esplanade reserves or esplanade strips for the purposes of protecting the water quality and biodiversity of the Wharemata River".

- Combined planning documents must identify what the objectives, policies and methods of the regional policy statement are, and clearly distinguish these from provisions of a regional or district plan.

- Where combined planning documents are not developed, regional councils and territorial authorities will need to work more closely in the development of the regional policy statement to ensure that district plans give effect to the regional policy statement. The process and mechanism to enable this are set out in clause 3A, schedule 1 of the RMA. The same can be said of involvement in the preparation of national policy statements.

- Those preparing and writing plans will need to carefully check and be prepared to incorporate issues, and possibly objectives and policies, from the national or regional policy statement.

- Section 32 reports will need to identify whether or not the national or regional policy statement have been given effect to in the plan and how. Where parts of the national or regional policy statement that are relevant to the plan are not given effect to, the s32 report will need to set out the reasons why not.

The permitted baseline in plans

The permitted baseline is a concept designed to disregard effects on the environment that are permitted by a plan or have been consented to. The three categories of activity that needed to be considered as part of the permitted baseline are:

- What lawfully exists on the site at present

- Activities (being non-fanciful activities) which could be conducted on the site as of right; i.e. without having to obtain a resource consent.

- Activities which could be carried out under a granted, but as yet unexercised, resource consent.

Existing use rights are not part of the permitted baseline as they are not permitted by the Plan however they may be important in assessing the receiving environment.

In its codified form, the permitted baseline test is most explicitly applied during the resource consent process when decisions are being made as to whether a consent application needs to be notified (i.e. deciding whether the effects are more than minor and who is affected), decisions on consents (s104), and in some enforcement matters.

The RMA refers to the permitted baseline specifically in three situations relevant to plan development:

- Section 104(2) states: "When forming an opinion for the purposes of subsection (1)(a), a consent authority may disregard an adverse effect of the activity on the environment if a national environmental standard or the plan permits an activity with that effect."

- Section 95D(b) provides that a consent authority when deciding if adverse effects will be minor "may disregard an adverse effect of the activity if a rule or national environmental standard permits an activity with that effect."

- The consent authority may disregard an adverse effect of the activity on the person if a rule or national environmental standard permits an activity with that effect (s95E(2)).

The use of the word 'may' in these sections conveys an element of discretion and it is therefore up to the decision-maker as to whether the permitted baseline test is used when assessing effects and identifying affected parties.

Consideration of the permitted baseline when writing plan provisions

The incorporation of the permitted baseline into plans should not have a noticeable effect on the way provisions look or are worded, although some of the requirements, conditions and permissions used may change. The greater effect is likely to be on the thought processes that go into writing rules for permitted activities and, to a lesser extent, other classes of activity (where these contain thresholds that distinguish between permitted activities and the relevant consent class). It will be important that plan writers not only have a clear understanding of the environment as it exists now, but also the environmental outcomes the plan is aiming to promote.

The following considerations may be useful for reflecting the permitted baseline in plan rules:

Permitted activities:

- Consider what the character of the existing environment or resource is and ask, "what is the maximum level of change to that character that should be permissible as of right?"

- In preparing or reviewing a set of rules, consider what the maximum permissible development or use will be, should all requirements, conditions and permissions in the plan (or proposed plan) provisions applicable to that area be taken to their limit on all (or most) sites. Such consideration should, however, take into account what may be realistic rather than fanciful. Ask:

- Are the effects resulting from development or use to the maximum limited permitted acceptable?

- Would the development or use permitted be consistent with the objectives and policies of the plan?

- Check to see if there are unimplemented resource consents for the site or area to which the permitted activity requirements, conditions and permissions will relate. How might these change 'the existing environment ' and the effectiveness of the provisions proposed? For example if consent has already been granted to develop resources more intensively than seen in the environment as it exist now, then the likelihood of the consent being implemented and the changed character of the environment - as it will exist - may need to be taken into account. However it will not always be practicable to undertake such a wide assessment when drafting rules.

Controlled activities

While the permitted baseline is intended to consider what is permitted 'as of right' by a plan, care may be needed drafting rules for controlled activities. It may be worthwhile to consider:

- the relationship of the controlled activity provisions being drafted with permitted activities. Are the requirements, conditions and permissions being used to define what qualifies as a controlled activity effectively defining the upper limits or thresholds for permitted activities? If they are, are the effects of development at those thresholds acceptable enough to be permitted? If the effects are unacceptable, consider revising the thresholds that qualify an activity for controlled activity status or imposing 'maximum ' limits for permitted activity requirements, conditions and permissions.

Possible plan numbering system

The following numbering system borrows from both conventional legislative drafting styles and the numbering system used in some New Zealand planning documents. Because plans may be divided up into parts and chapters and then issues, objectives, policies and rules, and the linkages between the latter need to be clearly shown, the 'multiple decimal point' style is adopted (the main point of difference from the numbering system used in legislation). This example is used for an issue-based plan that cascades from issues, to objectives, policies and then rules. Note that other plan formats cluster rules stemming from several issues, objectives or policies together in separate chapters.

|

Plan part or position in provision hierarchy |

Numbering style |

Example |

|

Parts of the plan |

Capital Roman numerals |

Part I: Plan purpose |

|

Chapters |

Standard numbering prefixed by 'Chapter' 1, 2, 3 |

Chapter 6: Subdivision issues |

|

Issues |

Standard numbering prefixed by 'Issue' 1, 2, 3 |

Issue 1: Unmanaged wash-down of effluent from dairy sheds in XYZ can adversely affect the water quality in ABC river. |

|

Objectives |

Standard numbering to two levels. For clarification the prefix 'Objective' can be added 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 |

Objective 1.2: There is no point source discharge of dairy shed effluent from drains in XYZ into the ABC River. |

|

Policies |

Standard numbering to three levels 1.1.1, 1.1.2, 1.1.3 |

1.1.1: Dairy shed effluent in XYZ should be disposed of via… |

|

Rules |

Standard numbering to four levels 2.3.3.4, 2.3.3.5, 2.3.3.6 |

2.3.3.4 The maximum height of any building or structure in the XXX zone shall not exceed… |

|

Subsection or part of policy or rule (note these can also be used for lists provided such lists are not within a subsection or part). |

Letters in brackets following alphabetical sequence : (a), (b), (c) |

2.3.5.1 Temporary activities are controlled in the CCC zone provided: |

|

Lists within policy (or rule) subsections or parts |

Lower-case Roman numerals in brackets (i), (ii), (iii) |

(d) A landscape plan is submitted that shall show: |

Some other tips relating to numbering

- Use the same style and hierarchy throughout the plan.

- If part of a policy or rule consists of two related lists, continue the second list as though it were a continuation of the first (that way there is no danger of the list items being confused through having two similar items). For example:

"Primary Productions includes:

- cultivation of land

- keeping and maintenance of animals, birds for the production of fibre, meat or other animal products

- fish and shellfish farming and hatcheries

- fruit, vegetable, flower, seed or grain growing but does not include:

- mining or drilling

- quarrying

- sand mining and shingle extraction".

- Consider breaking lengthy rules up into several separate rules if there are multiple lists and sub lists within the same rule.

- When referring to other provisions or parts of provisions use the short form of the number in italics (i.e. 2.3.1.6(a)(ii) ) rather than spelling it out in full (rule 2.3.1.6 paragraph (a) subparagraph (ii) ).

- Don 't use bullet points or dashes in policies and rules as these are confusing and difficult to reference.

- carefully the range of matters over which the council is to retain control and how much discretion is allowed for. Is the range of control so narrow and the outcome so certain that the provisions are, in effect, a permitted activity?

Cascade approaches

Cascade approaches are a way of organising plan provisions so that:

- it is easy to check relations between issues, objectives, policies and rules, and to see if they are consistent with each other

- plan drafters and those implementing the plan can check rules to manage the effects of activities through assigning activity status without leaving gaps or overlaps that create uncertainty or unintended outcomes.

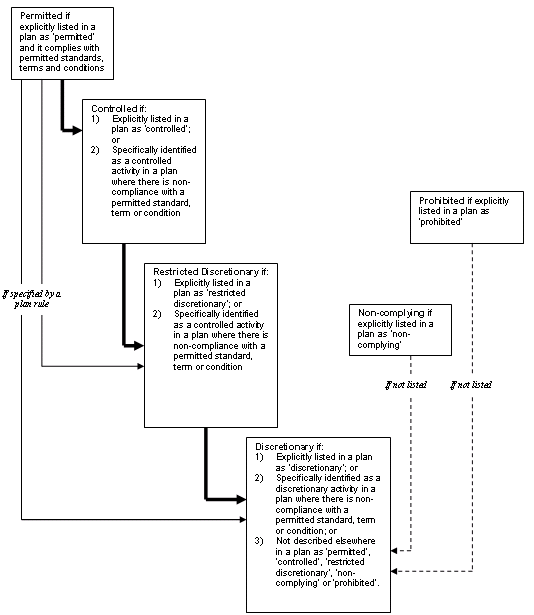

Cascades for checking internal relationships and consistency

A cascade approach can be used to check the internal consistency of provisions within plans. Characteristics of a cascade approach:

- objectives link back to issues

- policies link back to objectives

- methods link back to policies

- environmental results expected link to objectives

- indicators link to environmental results expected

- rules link to policies and methods.

This cascade approach simultaneously demonstrates both the 'top-down' approach to plan drafting and 'bottom-up' approach to plan interpretation, thereby indicating the close links the levels of plan components have with each other.

Relationships between plan provisions:

- objectives should be related to an issue (the issue may or may not be stated in the plan)

- policies should link to objectives (policies are the course of action to achieve one or more objectives)

- methods should link to policies (they are the techniques for implementing the policies) noting that methods (other than rules) may or may not be stated in the plan

- rules should link to policies (rules should also take into account other methods and may link to those methods)

- environmental results expected should link back to policies and methods (as they will provide a means of testing whether the policies and methods have achieved the desired outcome or objective) noting that environmental results expected may or may not be contained in a plan (if not, they may form part of the plan effectiveness monitoring required under s35)

- indicators should link to environmental results expected (indicators can be prescribed by regulations under the RMA to monitor the state of the environment - s35(2)(a)(ii)).

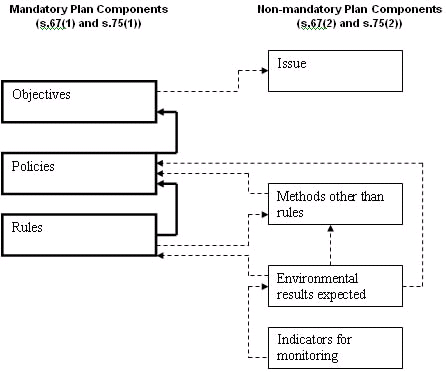

A cascade approach illustrating the mandatory and non-mandatory components of a plan could take the following form:

Cascades in plan rules

In relation to rules, a cascade approach is often used as a means to allocate an activity class to an activity according to the severity of effects (known or possible), or indicate the consequences of non-compliance with any requirements, conditions, or permissions associated with a particular activity class.

In allocating activity status according to severity of adverse effects, a cascade approach can act as a sieve whereby activities with the least potential for significant adverse effects are classified as permitted activities. Activities with some potential to cause a range of known, but relatively moderate, adverse effect may be classified as controlled or restricted discretionary activities. Activities with greater potential to cause more severe adverse effects are typically classified as discretionary, non-complying, or prohibited activities (according to the acceptability of the effect, the degree to which it can be remedied or mitigated, or whether the plan envisages activities with those effects). This allocation of activity status will often be demonstrated through:

- explicitly listing activities under a particular activity status

- incorporation of 'qualifying' requirements, conditions, or permissions with which the effects of an activity must comply for the activity to be allocated that activity status

- a combination of (i) and (ii) above.

In managing the consequences of non-compliance with a requirement, condition, or permission, a cascade approach is also used to decide what activity class the activity will consequently be considered under. For example an activity that fails to meet the requirements, conditions or permissions necessary to qualify for permitted activity status is allocated another activity status (controlled, restricted discretionary, or discretionary) by virtue of its non-compliance. This approach is commonly seen in wording in plan rules such as:

"12.3.3.5 Activities that do not meet the requirements set out in rule 12.3.3.4 will be considered as a discretionary activity under rule 14.5.5.5."

Or:

"14.5.5.5 Discretionary activities:

Any activity that does not comply with the requirements, conditions and permissions set out in rule 12.3.3.4".

Or:

|

Activity |

Requirements, conditions, permissions |

Matters over which council reserves control |

Non-compliance with requirements, conditions and permissions |

|

Controlled Activities Rule 13.3.4.5 Extensions to buildings in Waipopo Character Area |

|

|

Discretionary |

As shown in the diagram , the discretionary activity class often represents the bottom of the cascade as it is often used as the 'catch all' or 'default' activity class for activities causing effects not already managed through other classes (or specifically covered by the plan - see RMA ss68(5)(e) and 76(4)(e)). Note also that activities that are not classified in a plan or those that require a resource consent but are not covered by a rule in a plan default to discretionary activities under s87B. A number of plans, particularly those prepared before 1997 use the non-complying activity class in a similar manner (as an alternative to the using the discretionary activity class).

Ideas for providing certainty in plan rules

Why do rules have to be precise and certain?

Rules have the force and effect of regulations (ss68(2) and 76(2)). In that regard rules must be complied with and are enforceable. The general public and applicants need to have certainty over whether a proposal complies with rules in a plan and that those rules will be applied in a consistent manner. Considerable cost and time can be spent on establishing compliance and pursuing enforcement action when rules lack certainty.

Rules that contain words or phrases of uncertain or ambiguous meaning run the risk of being voided as ultra vires on the grounds of uncertainty.

Making rules precise and certain does not mean that there cannot be some flexibility. However, where flexibility is too great problems can arise. Rules should be sufficiently certain to be understandable and functional.

The golden rule of certainty

Draft rules according to plain English principles.

Some quick tests that could be applied

If the rules prepared match one or more of the following points then an amendment may be required.

- The rule creates uncertainty as to when or where it is to be applied (For example if the word 'there' is used, is it clear where 'there' is?).

- It is unclear what activities or effects the rule applies to.

- The rule conveys an element of discretion where none is intended.

- The rule is a standard, a threshold, or triggers another consent or activity class, and there is the potential for doubt as to what exactly the threshold or trigger point is, or how it is to be measured.

- The rule gives powers of determination (such as whether an activity will be classified as permitted or not) to a third party such as a neighbour.

- In regard to controlled or restricted discretionary activities, it is unclear or is there ambiguity over which matters the council has retained control or discretion.

Words and phrases to avoid in rules

Some words and phrases convey more flexibility and discretion than others. The following words do not allow for clear measurable tests or thresholds and may result in difficulties in assessing compliance or enforcement of the plan (unless they have been clearly defined in the definitions chapter of the plan or another associated rule):

- reasonable (e.g. "a reasonable amount of vegetation should be retained on-site")

- appropriate (e.g. "colours shall be those appropriate to")

- approximate (e.g. "shall be approximately 10 metres from")

- inappropriate (e.g. "inappropriate stream crossing by livestock shall")

- should (e.g. "the materials used should match those of the surrounding…")

- significant (e.g. "should be set back a significant distance from…")

- might (e.g. "any activity that might detract from")

- existing (e.g. "shall be measured according to the existing water levels for the lake") - it is better to have a reference to a particular point in time (or referenced water level) than to use 'existing' due to the variable nature of the environment.

The following phrases are inappropriate for permitted activities or rules which trigger a new consent/activity class as they convey an element of subjectivity or discretion:

- "at the discretion of the [council, manager of planning, engineer etc]"

- "to the satisfaction of the [council, manager of planning, engineer etc]"

- "avoid, remedy or mitigate" (eg "earthworks shall avoid, remedy or mitigate adverse effects on the archaeological sites")

- "as it sees fit"

- "where practicable" (e.g. "earthworks shall, where practicable, avoid sediment")

- "best practicable option"

- "and/or" (use one but not both).

Use of 'not withstanding'

Some plans use the words 'not withstanding' to indicate that where provisions conflict, one rule is to prevail over the other. While this can be useful when possible conflicts cannot be foreseen, it can create difficulties when the phrase is used often. Where a possible conflict is known, consider using something similar to:

"Where compliance with rule 13.4.2 would contravene rule 14.6.4, then the requirements of rule 13.4.2 shall prevail".

This then removes the possibility (for example) that a 'not withstanding' statement for rule 13.4.2 will come into conflict with another 'not withstanding' rule, or is inadvertently used as a way of getting around another rule that needs to be applied.

May - Must - Shall

'May' should be used where a power, duty, permission, benefit or privilege is given to some person, but need not be, exercised (i.e. the exercise of the duty, or permission is discretionary).

"…in considering an application under rule 13.4.5 the council may consider…"

'Must' should be used where a duty is imposed which must be performed.

"…a filter system complying with the standards contained in rule 15.3.2 must be fitted to the outlet…"

'Shall' is used to impose a duty or a prohibition, but can also be used to indicate the future tense. This can lead to confusion. 'Shall' can be replaced by 'must' where confusion may occur.

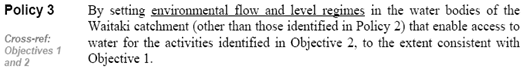

Cross-references in RMA plans

Cross-referencing may take one of a number of styles such as:

- direct references to another plan provision from within an objective, policy or rule

- side notes

- tables of cross-references

- lists.

In on-line or electronic plans, bookmarks and hyperlinks are commonly used to enable the reader to be taken directly to the provision being cross-referenced.

The RMA makes no mention of cross-referencing within plans, though part 3 of schedule 1 includes clauses relating to the incorporation of external material into plans by reference. References to national environmental standards can be included without using the process in schedule 1. Good cross-referencing has become essential as plans are complex and plan users often need direction to assist them in finding their way around, or knowing what other provisions they need to refer to.

Direct references within plan provisions

This method is commonly seen in statues and regulations, and most often in plans when only one or two provisions are being referred to. For example:

"Activities in the Erehwon valley must also comply with the standards relating to earthworks contained in rule 10.3.4.3",

or

"In considering an application for a consent under rule 6.6.1.2 the council will have regard to the matters of assessment set out in Policies 6.6.8 and 6.6.9".

The advantages of this approach are:

- useful for providing a clear, direct, link from a rule to another plan provision when that other provision is intended to form part of the rule

- does not require changes to page layouts or additional pages to be set aside

- can be located within provisions so are clearly associated with those provisions

- does not require additional effort to format when producing an on-line (website-based) plan.

The disadvantages of this approach are:

- not very good at referencing multiple provisions if located in many parts of the plan

- cross-references tend to get 'hidden' in text or mistaken for other material

- can add to the length of plan provisions, making them harder to read

- can sometimes get mistaken for being plan provisions in their own right.

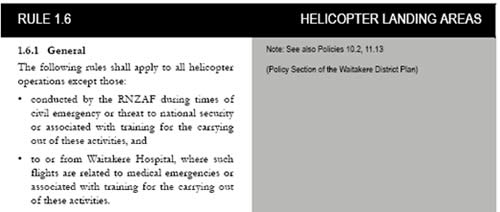

Side notes

The side note sees the side margins of the page used to display cross-references. Several variations of this see the cross-references either highlighted through techniques such as shading or italicised text, for example:

From the former Waitakere District Plan:

From the Waitaki Water Allocation Regional Plan:

The advantages of this approach are that it:

- provides a clear and distinct indication of what is being referenced to

- does not become confused with other numbers in plan provisions

- is able to cross-reference multiple provisions if space permits

- permits references to be made to documents outside the plan (such as methods being located in another plan or strategy for example)

- can be easily combined with the 'direct reference within provisions' approach if required.

The disadvantages of this approach are that:

- it uses more space than the 'direct reference' technique

- columns can be a problem for some on-line plans and some software, computer or screen settings have difficulty in displaying them in a reader-friendly format

- lengthy lists can get out of sync with the provisions they are cross-referencing from.

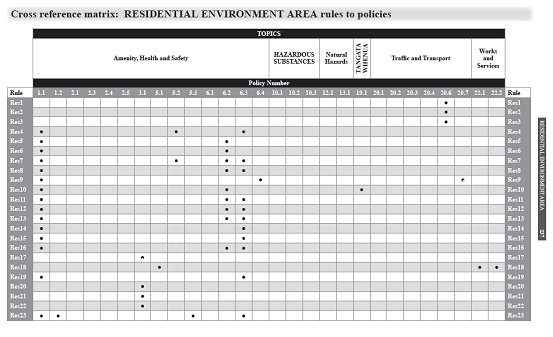

Tables of cross-references

Another approach to cross-referencing is to have tables at the start or end of each chapter (or possibly at the start or end of the plan provisions) that summarise all the linkages between provisions as shown in the following example. 216.8 Policy linkages table

|

OBJECTIVE 216.3.1 |

OBJECTIVE 216.3.2 |

OBJECTIVE 216.3.3 |

OBJECTIVE 216.3.4 |

|||||||||

|

Maintain and develop an efficient and safe road and air transportation network that meets the needs of the District's community |

Protect critical areas of interface between land and water that enable passenger and goods transport by sea. |

Minimise the adverse effects of the transportation network on people and the environment. |

Ensure activities do not adversely affect the safe and efficient operation of the transportation network. |

|||||||||

|

Given Effect to by Policies |

||||||||||||

|

216.4.1 216.4.2 216.4.3 216.4.4 216.4.5 216.4.6 216.4.7 216.4.12 216.4.13 |

216.4.8 216.4.9 216.4.11 |

216.4.1 216.4.6 216.4.7 216.4.8 216.4.9 216.4.10 216.4.12 216.4.13 |

216.4.1 216.4.2 216.4.3 216.4.4 216.4.5 216.4.11 |

|||||||||

|

Environmental Results Expected |

||||||||||||

|

216.7.1 |

216.7.1 |

216.7.2 |

216.7.3 216.7.4 |

|||||||||

|

Policy |

||||||||||||

|

216.4.1 |

216.4.2 |

216.4.3 |

216.4.4 |

216.4.5 |

216.4.6 |

216.4.7 |

216.4.8 |

216.4.9 |

216.4.10 |

216.4.11 |

216.4.12 |

216.4.13 |

|

Implemented by Methods |

||||||||||||

|

216.5.1 216.5.7 |

216.5.1 216.5.2 |

216.5.2 |

216.5.2 |

216.5.4 |

216.5.2 |

216.5.6 |

216.5.5 216.5.6 |

216.5.1 216.5.2 216.5.3 216.5.4 216.5.7 216.5.8 |

216.5.2 216.5.8 |

216.5.2 |

216.5.3 216.5.7 |

216.5.3 |

New Plymouth District Council uses a check-box like matrix table to provide cross-references at the end of chapters in their plan. This derivation of the table approach is simple to operate in checking rules against policies, but is less able to show the flow through from objectives, or the environmental results expected.

The New Plymouth District Council gets around this latter problem by setting out their policy chapters in a sequential issue-objective-policy-method fashion for each issue so the policy becomes the key linkage mechanism.

The advantages of the table approach are that it is:

- able to provide the 'big picture' overview of how a large range of provisions relate and link

- able to provide transparency in the flow of provisions from issue identification to methods and rules.

The disadvantages of table approach are:

- it can-not easily provide linkages between chapters related to other issues

- dealing with multiple issues can lead to large tables that are not able to be accommodated on a single page

- it can be difficult to format and view on-line, depending on software used and user computer settings

- it is less capable of indicating when methods are located outside plans, and where those methods can be found.

Lists

Lists are essentially similar to the side note approach to cross-referencing, through are often found at the end of a particular provision or chapter as part of the main text rather than in a margin. A typical example might be:

Rule 3.4.3.5

The taking, diversion, or use of water from the Waipuku River for agricultural and horticultural purposes must meet the following standards:

- The rate of abstraction per lot must not exceed 1.0 litre per second;

- The total rate of abstraction for a combination of lots under the same certificate of title must not exceed 15 litres per second.

- The flow of any diversion must not exceed 5 cumecs

Cross-ref:

|

Objectives |

3.4, 3.5, and 3.7 |

|

Policies |

3.4.1, 3.4.3, 3.4.4 |

|

|

3.5.2, 3.5.4 |

|

|

3.7.3 |

|

Rule: |

2.5.3.3(general rules for diversions) |

|

Other methods |

3.4.1 methods(i), (ii), and (iii) |

The advantages of this approach are, that it is:

- able to show a vast array of information while keeping the references aligned in sync with the provision being referenced from

- able to reference to multiple provisions in different parts of the plan or to external documents.

The disadvantages of this approach are, that:

- lists can be repetitive and add to plan length if used for each provision

- lists at the end of chapters can be overlooked

- in terms of visual appearance, lists may be mistaken for being part of the plan provision.

Ideas for the use of plain English in plans

What is 'plain English'?

Plain English is clear, straightforward expression, using only as many words as are necessary. It is language that avoids obscurity, inflated vocabulary and convoluted sentence construction. It is not baby talk, nor is it a simplified version of the English language. Writers of plain English let their audience concentrate on the message instead of being distracted by complicated language. They make sure that their audience understands the message easily.

(Professor Robert Eagleson -University of Sydney)

Writing plans in plain English does not mean avoiding complex information to make a plan easier to understand. For plan users to make informed decisions, planning documents may have to convey complex information. Using plain English assures the orderly and clear presentation of complex information, so that plan readers have the best possible chance of understanding it.

Plain English means analysing and deciding what information plan users and decision makers will need to make informed decisions, before terms, provisions, or explanations are used.

Key principles

The 10 most important principles in plain English writing are:

Sometimes you can use a simpler word for these phrases:

|

Phrase with redundant words |

Replace with |

|

in order to |

to |

|

in the event that |

if |

|

subsequent to |

after |

|

prior to |

before |

|

despite the fact that |

although |

|

because of the fact that |

because |

|

in light of |

because |

|

owing to the fact that because |

since |

|

as to whether |

whether |

|

The said parties |

The parties |

|

Legalese, complex or archaic |

Simpler |

|

pursuant to |

under |

|

prior to |

before |

|

terminate |

end |

|

elucidate |

explain |

|

utilise |

use |

|

deemed |

regarded/treated as |

|

in lieu of |

instead of |

|

in like manner as |

in the same way |

|

otherwise than |

except |

|

hereinafter |

as follows |

Abbreviations should be avoided as they can lead to confusion or misdirect people to documents, policies etc. that are out of date. If there is likely to be any doubt, spell it out.

- Think of your reader's needs - what is it that they need to know? What level are they reading at? (See also principle 8.)

- Organise your content well - have a clear structure and know what your key message is

- Write in a natural style, as if you were talking to the reader - this assists in flow and simple sentence structure. Care needs to be taken to avoid colloquialisms.

- Keep sentences short -this avoids making the reader process too many ideas at once. It also reduces the risk of confusion over the relationships between verbs, adjectives, and subjects. It helps if you keep each sentence to one key topic.

- Use active verbs and try to avoid lengthy noun phrases where possible (for example "the Court decided" is better than "it has been decided by the Court"; and "a decision to amend a regulation by the district council" is better than "a district council regulation amendment decision")

- Be specific rather than general - for example instead of 'regularly' specify time intervals (monthly, quarterly, yearly)

- Cut all redundant words and phrases - ask yourself if the word or phrase is needed for grammatical correctness or is important to get the message across. Words are redundant when they can be replaced with fewer words that mean the same thing.

- Use simpler words rather than complex words - avoid archaic words unless there is no word of accepted equivalent meaning. For example:

- Cut down on jargon and acronyms. However for legal and interpretative reasons it is advisable that plans use the same terminology and phrases as contained in the RMA. These terms and phrases often have specific legal meanings and an established body of case law behind them that assists in interpretation. If you have to use a term not in common usage then ensure it is defined in plain English terms in the definitions section.

- Edit vigorously - never underestimate the value of one or more ruthless edits. Look at each phrase and ask if there is a simpler, more direct, way of expressing it. Get someone who was not involved in the writing to read through and see if they can understand what is being said.

Other tips

- Write 'in the positive'- positive sentences are shorter and easier to understand than their negative counterparts. For example use 'is similar to' instead of 'is not dissimilar to'.

- Replace a negative phrase with a single word that means the same thing. For example:

|

Negative compound |

Single Word |

|

not able |

unable |

|

not accept |

decline |

|

not unlike |

similar |

|

does not have |

omits |

|

not many |

few |

|

not often |

rarely |

|

not the same |

different |

|

not ...unless |

if |

- Use lists where appropriate - lists are excellent for splitting information up, making it easier to read and understand the content of the list. There are two main types of list.

- You can have a continuous sentence with several listed points picked out at the beginning, middle or end.

- You can have a list of separate sentences with or without an introductory statement (like this list).

For a list with short points, plain English editors suggest setting it out like this:

The matters over which the Council retains control are:

- vehicle access

- clearance of vegetation

- volume of earthworks.

Lists may be bulleted, or numbered in various formats. Those comprising separate sentences have an initial capital and normal punctuation. Lists that are part of a continuous sentence may have semicolons (;) after each point and start each point with a capital. Ministry for the Environment style uses lower case for such items and only a full stop after the last item in the list. Many valid styles exist - the main thing is consistency within each document.

Adapted from:

New Zealand Law Commission (1996) Legislation Manual: Structure and Style, Report 35, Law Commission Wellington.

Office of Investor Education and Assistance (1998) A Plain English Handbook U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Washington DC.

With particular reference to legal writing:

Clarity: an international association promoting plain legal language

Promoting internal consistency in RMA plans

Why consistency is important

Consistency within and between plans promotes certainty and familiarity and lessens problems associated with interpretation and unintended consequences. More specifically, use of the same phrases and terminology:

- means that experience gained in the application or implementation of provisions in one part of the plan, can be applied more easily to other parts of the plan where that term or phrase is used

- increases certainty in interpretation, as readers don't have to think about whether slight variances will result in significant changes of meaning; and there is less likelihood of misinterpretation

- improves the ability of new staff to quickly understand the structure of the plan and the way in which provisions in it are to be interpreted.

Ideas for promoting internal consistency

Drafting protocols/guidelines/style guides

These are documents produced within the council itself and combine legal requirements, good practice, and council requirements for plan provision drafting into a style guide. The document then becomes a key reference for all those involved in drafting plan provisions to follow. Drafting protocols and guidelines may contain:

- an explicit statement of what the protocol or guidelines are designed to achieve

- the goals adopted for the drafting of the plan (such as the philosophical approach taken to the permissiveness or restrictiveness of the plan, the degree of simplicity in language and standards desired, or what the plan should be working towards achieving)

- the principles to be followed in drafting the plan

- an outline of the plan format and how provisions are intended to relate to each other

- examples that illustrate the style in which provisions are to be drafted

- protocols in regard to reviewing and checking against the guidelines or protocols (such as whether a style champion has been appointed or not, what the roles of the champion are, or protocols regarding peer reviews and self-checking).

Good practice tips for drafting protocols and guidelines include:

- approach writing the content of the guideline or protocol from the perspective of a staff member who has recently joined the council but has some RMA experience already (don't assume staff already have knowledge of how the local authority does things or how provisions have been written in the past)

- include examples of what is meant wherever possible

- ensure everyone who will be involved in drafting has an opportunity to input into the drafting before the guidelines or protocols are finalised. This is important to maintain a sense of ownership, commitment and understanding of why the document exists and what it contains

- involve consent planning staff in developing the protocol or guidelines. What do they want to see included? What do their experiences in using existing plans tell you about what needs to be included or avoided in the next plan?

Style 'champions' and watchdogs

Appointing a person within the drafting team who monitors and checks for issues of consistency in style, terminology can assist. This person has the role of ensuring others are reminded of, and are adhering to, the style, phrasing and terminology chosen for the plan. In the past this task has often been the de facto role of the project leader or manager, but it can be given to any experienced person within the drafting or editing team. In using this technique it is important that:

- this champion is fully aware of all the style requirements adopted by the council and good practice in plan provision drafting

- the champion has some form of guide or objective set of criteria that serve as prompts or reference checks that can be used by both the person doing the initial drafting and the champion in checking

- processes are in place that ensure this person sees and has time to check and amend (or make recommendations on) all plan provisions, changes, and variations before they reach the notification (or council approval) stage

- the person chosen is able to provide constructive feedback on style and what is needed to keep it consistent

- all members of the drafting team accept the role of the champion and are comfortable with it (reminders may need to be given periodically to the effect that the champion is there to assist in ensuring a consistent end product that meets pre-agreed standards).

Style and content edits

As well as checking and editing to eliminate grammatical and technical errors, a dedicated edit for consistency of style and content may be carried out. Checking against the drafting protocol can assist with this. Other good practice ideas for checking content and style include:

- using a professional editor, technical writer, or journalist to read through the document and see if they can pick up inconsistencies in style, or suggest ideas to make the plan easier to read (they are usually very familiar with the principles of the plain English writing style).

- ensure that new provisions are peer-reviewed by a person who is familiar with the plan (the writer may see what is supposed to be there, rather than what is actually written).

Legal review

Legal reviews are usually carried out to check the legality and robustness of policy statement or plan provisions. In checking provisions, lawyers can also pick up on inconsistencies in the way provisions are expressed and on terminology of legal principles and case law. As legal reviews typically come towards the end of the pre-notification drafting phase, they should not be relied on as the primary method of checking consistency. Also, having a lawyer check for style and consistency of wording throughout a plan may not represent the best use of the lawyer's time or expertise. It some circumstances having a lawyer just look at key phrases that are used throughout the plan, or wording concerning areas that a particularly contentious, may be more cost-effective.

- If your council has adopted and documented a particular style, make sure that the lawyer is aware of this (perhaps by circulating a copy of drafting guidelines or reports that set out the adopted style). Ideally lawyers should have been party to the development of that style.

Templates

Some councils use templates in place of, or as part of, style guides. Electronic templates can be used to ensure fonts are appropriate to the various level of headings, and general plan text. More advanced electronic templates can assist in numbering plan provisions, and can also contain prompts to remind the writer of key considerations or tasks when drafting.

Testing issues for RMA Plans

Why test issues?

Not all issues that come to a local authority's attention need to be addressed through RMA plans, and not all issues will require a regulatory response. Regional and district plans are part of a much larger suite of tools that are available to address matters.

Incorporating issues into plans without first testing them can result in plans that are unnecessarily complex or lengthy, or that tend to over-regulate. This could add costs to the community and the council through the extra effort needed to research and write provisions for the plan, and additional consent applications subsequently needing to be lodged.

There is no need to list everything that appears to be an issue in a plan. Issues need to be tested to determine if it really is an issue, and whether it warrants inclusion in the plan. To do this a series of questions can be asked in relation to each potential issue.

Is there really an issue?

Before even thinking about resolving an issue there is a need to be clear that it does in fact exist. Questions that can assist in testing this include:

- What factual evidence supports that the issue exists and that it is causing or is likely to cause effects? For example are there:

- independent, credible, witnesses?

- observable evidence?

- technical reports relevant to the district or region that identify the issue?

- Are the effects generated positive or negative?

- if the effects are positive - do you want, or need, to manage it?

- are there side effects or consequential effects that need to be managed?

- If the issue has not yet occurred, is there a realistic chance of it occurring within the lifetime of the plan? In the case of issues or effects that are cumulative or may not manifest themselves for some years a supplementary question could be "would managing the issue now avoid or mitigate the effects in future?" To assist in answering this question consider:

- Are there relevant precedents that can be drawn on?

- What credible evidence exists, indicating the probability of the issue causing effects in the lifetime of the plan?

- What evidence is there to indicate that intervention through an RMA plan will be effective in avoiding or mitigating effects in the long term?

- Is the issue related to an opportunity (for example a change to enhance amenity or biodiversity)? If so:

- Does the council need to actively manage the opportunity or will it occur without council involvement?

- Will council involvement add value or improve the quality of the outcome?

- Is the opportunity best managed through an RMA plan or would some form of cooperation, action, or agreement outside the plan be more effective?

Symptom or cause?

Sometimes what is being presented as being an issue is the symptom rather than the issue. It is important not to take things at face value and look further into the circumstances around the issue:

- Why is there an issue?

- What events led to this becoming an issue?

- Are there matters beyond the immediate site or area that are contributing to the issue? If so, how did these matters come about?

Answering these questions helps to identify whether there is an issue and how to address it. Notably, reverse sensitivity situations often give rise to complaints that present the symptoms but not the real cause. For example repeated complaints regarding noise from farming operations may not be the result of increasingly noisy machinery, but the fact that recent residential development has introduced into an area more people sensitive to the noise of existing operations.

There are several techniques that can assist in revealing the underlying issue such as:

- 'Five whys': Start with what appears to be the issue, and ask why it has occurred (or why it would occur). Take the answer to your first question, and ask why those circumstances occured. Repeat the exercise (usually up to five times) until you have a revealing answer or have found it impossible to answer 'why' again.

- 'De Bono's Hats ': Approach the issue from several angles in terms of the key parties. What might be motives for each party? What are they trying to promote or avoid? Whose motives conflict and why?

- Consultative processes (e.g. focus groups). Triangulation in consultation (i.e. actively seeking the views of parties on both sides of the issue, and independent observers) can assist the plan writer verifying the legitimacy (or otherwise) of an issue and possible causes.

How significant is the issue?

Once the real issue has been identified, the next step is gauge how significant the issue is. If the issue is insignificant, it may be an inefficient use of resources to deal with it through a regional or district plan.

At present there are no formal guidelines that objectively distinguish what issues are significant to a region or district. Consultation either through the RMA or LGA processes can assist in determining what is important to a community generally. However the community may not be aware of all issues that are significant, or may miss the significance of issues that do not receive media coverage or publicity.

Asking the following questions may assist practitioners in determining the significance of an issue:

- Does the issue specifically relate to any of the matters contained in sections 6-8 of the RMA?

- Does the issue threaten or undermine a heritage order or water conservation order?

- Has there been widespread public concern expressed in relation to the issue? (Have there been many, repeated, complaints or submissions in regard it, or just a few?)

- Is the resource or feature to which the issue relates an icon for the district or region?

- What is the nature of the resource that is being affected? (For example an issue could be significant if it affects a rare or endangered resource, or a resource that is highly valued by the community and which cannot be replaced once gone.)

- Does the issue concern a resource or feature that plays a crucial role in enabling people in the region or district to provide for their social, economic and cultural wellbeing?

- Has the issue been identified in a technical report or other expert advice as being significant? (For example, has a report identified a particular area prone to major flooding?)

- What is the scale or level of risk of the effects associated with the activity? (An issue affecting one pine tree is not likely to be as significant as one affecting many hectares of endangered forest.)

- What is the extent of the activity? (Think geographically or in terms of the number of people affected.)

- Is it a significant cross-boundary issue? Does it require coordination through a regional policy statement or a combined planning document?

Whose issue is it?

Having identified that an issue exists and that it is of significance to require action, a logical next question in determining whether it should be included in an RMA plan is to check who has responsibility for the issue. A vast range of issues are dealt with by authorities or agencies other than councils. Examples of other agencies include:

- Civil Aviation Authority

- Department of Conservation

- Health Boards

- Maritime Safety Authority

- Ministry for Primary Industries

- Ministry of Bussiness Innovation and Employment

- Ministry of Health

- New Zealand Police

- New Zealand Transport Agency

- Another tier of local government.

Questions that could help guide thinking in terms of deciding whose issue it is include:

- Is the issue within the functions given to the council under s30 or s31 of the RMA? (If not, then it should not be controlled through an RMA plan.)

- What other legislation may be the primary statute for managing the issue, and who is responsible for administering that legislation?

- Are the existing legislative provisions and authorities sufficient to manage the issue? (If not, then consider whether there is an overlap or gap and whether the RMA plan has a role in managing the overlap or gap.)

What ways are there to manage the issue?

Having established that the issue is one that needs to be managed, and is the responsibility of the council, the final question asks if there are other means available to the council, so that dealing with it through a RMA plan is not necessary. Such other means could include:

- annual plan projects (the funding allocated could advance or delay an infrastructure project, for example)

- reserve management plans or acquisition of land for reserves.

- covenants

- asset management plans

- financial incentives (such as rates relief)

- delegation of functions or transfer of powers (ss33 and 34A)

- education programmes

- memoranda of understanding, or agreements

- engineering standards and codes of practice

- liquor licensing

- bylaws.

Note that the list above is not mutually exclusive: more than one means (including plan provisions) may be employed to deal with different aspects of the same issue.

Zoning as a tool in plans

Zoning is a long-used technique used to divide areas of land or water into distinct areas in order to manage effects, activities or uses. Zoning has been described as allowing “the district plan to create bundles of activities considered generally appropriate in each zone or area, in recognising the constraints of the environment and that some activities may not be appropriate in every location".

While the terms 'environments', or 'management areas' are sometimes used in place of zoning, the principles and objectives are essentially the same, for example:

- management or separation of incompatible uses

- avoidance of hazards

- identification and management of areas where similar outcomes are sought or bundles of effects need to be managed.

The technique of zoning has been criticised by some as being too directive or inflexible, however the fact remains that differentiation of any regulations according to geographic areas results in something that is analogous to a zone. In many cases analysis of the criticism of zoning shows that it is the regulation rather than the zoning triggers that are at issue (not the idea of the zoning itself), or the way in which some councils have allocated or changed zoning that is of concern.

Legitimacy of zoning as a tool under the RMA

While there have been numerous Environment Court cases dealing with zoning, most have related to the appropriateness of a certain zone, or rules that the zone triggers. Few cases have challenged zoning as a tool for use in RMA plans, and none have found that zoning, as a tool or method, is inappropriate within the context of the RMA. But what is also clear from case law is that zoning is a technique or method to achieve the objectives and policies of a plan, and is not an outcome in itself.

Practice in zoning under the RMA

Do:

- treat zoning as being a method to geographically delineate those areas where certain effects are acceptable or not acceptable, or where certain management tools are to be applied

- test proposed zoning in terms of:

- its appropriateness in reflecting current uses

- whether the zoning is appropriate to achieve the purpose of the RMA and objectives and policies of the plan

- whether the proposed zoning achieves integrated management of the effects of the use, development, or protection of the land or water ; and

- whether it controls the potential effects of the use, development, or protection of the land or water.

Avoid:

- using zoning under previous plans as an automatic starting point without reviewing whether such zoning is still the most appropriate management approach under a new plan or plan change

- zoning land to allow an activity when the infrastructure necessary to allow that activity to occur without adverse environmental effects does not exist, and there is no commitment to provide it.

Scheduling as an alternative to 'spot zoning'

In some cases existing uses within a particular zone are of a nature that would be inconsistent with the zone objectives and policies. While the existing character of the use can be recognised under RMA s10, any changes to the activity may require multiple resource consents to be lodged to ensure its lawfulness. In the past some plans have introduced 'spot zones' that apply certain development opportunities and controls to just one or two sites to get around this problem.

The inherent danger in spot zoning is that the number of spot zones can quickly multiply and overly complicate the plan. An alternative approach is to 'schedule ' certain sites to allow for their continued use and development, within certain parameters to ensure the acceptability of environmental effects. Some of the factors for adopting scheduling could include:

- agreements between stakeholders as to the use of the technique

- ability to identify particular sites

- ability to develop the formal standards and/or criteria for operation

- the nature of the activity and its scope

- potential impacts

- available resources on which scheduling would depend.

A schedule could take the form of a table in the plan conveying the following information:

- scheduled site number (if there is more than one site on the schedule)

- applicable planning map reference (number)

- permitted activities for the site

- legal description of the site

- conditions applicable to the site and permitted activities.

This material would be accompanied by a general statement explaining the reasons for adopting the method and its purpose, together with such objective(s) and policies as deemed appropriate and explanatory material describing how the schedule operates.

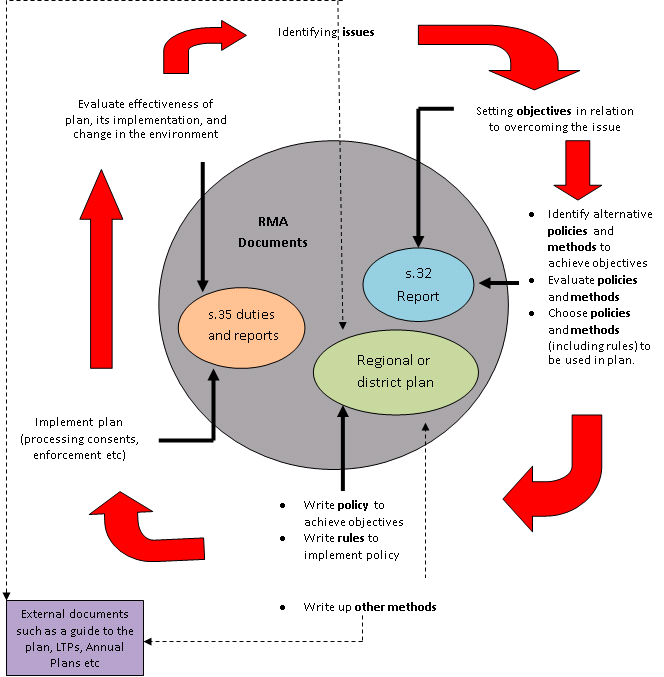

The planning process cycle under the RMA

The key steps in the public policy cycle are also logical steps in plan development:

- identifying the issue

- setting objectives in relation to the issue

- choosing and evaluating the policy and methods to achieve the objective

- implementing the policy and objectives through the chosen methods

- monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the policies, methods, and the environment.

A plan needs only to contain objectives, policies and rules. However, the complete planning process is a logical model to use in plan development and monitoring, and many of the steps are implicit within the duties and requirements of other sections of the RMA (such as ss32 and 35). Provisions, other than objectives, policies and rules can be contained in external documents. The diagram below shows such an arrangement.

Section 79 allows councils to amend any provision of regional or district plans. The section also requires councils to review provisions of regional and district plans at least every 10 years; in so doing councils can choose to amend only the parts of the plan that need to be amended, to be brought up to date. The above planning policy cycle process is equally applicable and relevant to such a rolling process.

- Issues: As an alternative to containing issues in the plan, these could be contained in s32 reports (forming part of the justification for provisions of the plan). It is difficult to evaluate the extent to which objectives are appropriate to achieve the purpose of the RMA without having reference to issues. Therefore issues are usually explicitly covered in s32 evaluation reports. Alternatively, issues could form part of the explanatory material in a guide to a plan. Such a guide may not have a statutory function, but would enable plan users to understand why certain provisions existed, and what effects were sought to be avoided, remedied or mitigated. It could also be referred to in making decisions on resource consents as an 'other matter ' under s104(1)(d).

- Objectives in relation to issues: These are mandatory in RMA plans, but each objective is also required to be evaluated (in terms of appropriateness) under s32(1)(a). Refer to the section 32 guidance for further information.

- Choosing and evaluating policies, rules and other methods to achieve the objectives forms a critical part of the s32 evaluation process to the extent that the policies, rules and other methods, and the justification for their existence, and the consideration of them against other potential policies and methods, will be covered. Having chosen the policies, rules and other methods to be used, these may then be drafted for inclusion in the plan. It is mandatory for the plan to contain the policies and rules (with rules being a method), but methods other than rules could be transferred to other documentation either as information (for example, in a guide to the plan) or as capital or operational programmes (in which case they may appear in Long Term Plans, annual plans, or asset management plans for example).

- The way in which plan provisions are implemented are not recorded in the plan itself. However s35 of the RMA requires councils to keep records of decisions made with respect to notification and service of notice decisions made on consents, and complaints about breaches of the RMA and RMA plans (amongst other things). This information forms an important resource for reviewing plan provisions and identifying new issues; a summary of it could appear in background reports to a plan review.

- Monitoring the effectiveness and efficiency of plans is also a mandatory requirement under s35. The results of this monitoring are required to be made available to the public at intervals of no more than five years. Information relevant to this duty, such as environmental results expected, can be placed in documents outside the plan (such as in s35(2)(b) reports). Refer to the guidance note on policy and plan effectiveness for further information.

Note: Use of a dashed line indicates items of the public policy or planning cycle that can be contained in plans at the discretion of a local authority, but are not mandatory.

Example issues

Regional plan issues

Issue 1

Discharges of contaminants from agricultural activities into rivers, streams and lakes in the Erehwon Region reduce water quality and can damage aquatic ecosystems by increasing the levels of suspended solids, nutrients and faecal coliforms.

Issue 2

Poorly managed earthworks and land clearance, and land cultivation accelerates erosion in the Waipopo hill country and contributes to decreased water quality in the Monowai River through increased sediment loadings.

Issue 3

Use and development in the coastal marine area near Port Whangarua can have an adverse on the navigation and safety of ships by obstructing the use of navigable waterways, altering water currents, or contributing to changes to the form of the coast and seabed through accretion and erosion.

District plan issues

Issue 1

Intensification of land use and development in the rural environment of Whatsup District can adversely affect the visual and scenic character, and health, safety and enjoyment of residents by changing the appearance of the area and increasing noise, vibration and traffic.

Issue 2

Increases in the area of land used for residential purposes throughout the Whatsup District can result in the loss of areas of significant indigenous vegetation, and the drainage of wetlands with high levels of biodiversity.

Issue 3

The use of land for more intensive forms of development in hazard-prone areas throughout the Whatsup District can exacerbate existing landslip, erosion, inundation and falling debris hazards, threatening the health and safety of residents and increasing the risk of damage to buildings and property.

Example plan issues, objectives and policies

Regional plan examples

Note: The first example deals with an issue that occurs throughout the fictional Erehwon Region. The second example deals with an issue that is discrete to one part of the Erehwon Region.

|

Issue 1: Discharges of contaminants from agricultural activities into rivers, streams and lakes in the Erehwon Region reduce water quality and can damage aquatic ecosystems by increasing the levels of suspended solids, nutrients and faecal coliforms. |

|

|

Objective 1.1 To reduce the level of suspended solids, nutrients and faecal coliforms in rivers, streams and lakes in the Erehwon Region resulting from discharges from agricultural activities to a level that maintains or enhances aquatic ecosystems. |

|

|

Policy 1.1.1 All dairy-shed effluent associated with farming activities near a river, stream or lake in the Erehwon Region should be disposed of to land, taking into account:

|

Refer to objectives 1.1 and 6.2 |

|

Policy 1.1.2 Land uses in the rural areas of the Erewhon region should retain or increase the proportion of lake shore and stream and river bank planted with riparian vegetation to act as a barrier or filter for diffuse source discharges and runoff. |

Refer to objective 1.1 |

|

Issue 2: Activities on, in, or under the bed of Lake Waeroa, including the building and location of structures, reclamation works, and extraction of gravel, can damage or destroy the ecology of the lake by contributing to erosion, sedimentation, plant life and fish spawning areas. |

|

|

Objective 2.1 To avoid further erosion or sedimentation of Lake Waeroa and the Lake Waeroa bed and damage to the ecology of the lake arising from activities that build, locate or operate on, in or under the lake bed. |

Refer to issues 2 and 6 |

|

Policy 2.1.1 Structures and activities in, on, or under the bed of Lake Waeroa should be located, operated and managed in such a way that avoids:

|

Refer to objectives 2.1 |

|

Policy 2.1.2 Any man-made disturbance to the bed of Lake Waeroa should be carried out in a location and at a time that will avoid or mitigate any adverse effects on fish spawning or migration. |

Refer to objective 2.1 |

District Plan examples

Note: The first example deals with an example of an issue that occurs throughout the fictional Whatsup District. The second example deals with an issue that is discrete to one part of the Whatsup District.

|

Issue 1: Intensification of land use and development in the rural environment of Whatsup District can adversely affect the visual and scenic character, and health, safety and enjoyment of residents by changing the appearance of the area and increasing noise, vibration and traffic. |

|

|

Objective 1.1 To retain and protect the significant landscape features and ecological areas that contribute to the scenic character of the Whatsup District rural environment. Objective 1.2 To ensure that new development is consistent with, and does adversely affect, the open, small scale development, character of the Whatsup District rural environment. |

|

|

Policy 1.1.1 All new development in the rural environment of the Whatsup District should be located in a position, or in such a way, that avoids adverse visual impacts on identified significant landscape features and ecological areas. |

Refer to objective 1.1 and Annex B. |

|

Policy 1.2.1 All new development in the Whatsup District rural environment should be of the same small scale and low density that constitutes the predominant character of the rural environment. |

Refer to objective 1.2 |

|

Issue 2: Noise from the Whatamata International Airport can have an adverse effect on the health and wellbeing of people living in the expanding suburb Whatamata West. |

|

|

Objective 2.1 To enable the continued operation of the Whatamata International Airport while ensuring the noise received by people living or working in Whatamata West is maintained at a level that does not compromise their health and wellbeing. |

|

|

Policy 2.1.1 Ground based activities and the operation of aircraft that is not immediately before or after flight should be managed to avoid adversely affect health and wellbeing of existing areas of Whatamata West. |

Refer to objective 2.1 |

|

Policy 2.2.1 New activities, land use and development around the Whatamata International airport should:

|

Refer to objective 2.1 |

Example District Plan rules

The following examples are hypothetical representations of rules written in accordance with best practice guidelines. While not shown here, cross references to policies and objectives would be appropriate.

The formats in the following rules are for example purposes only. Their purpose is to demonstrate how rules could be worded and possibly linked within a rule and to other rules.

An alternative to listing activities under each activity class is to tabulate them. Some existing plans take this concept further by having all the rules written up as a table.

Tables

A table that outlines rules is useful for two reasons. First, it can be used as a drafting tool to test the thresholds for rules. It provides an effective way of checking rules that overlap or repeat, and finding gaps. It also lets practitioners review the cumulative effect of all the rules applicable (eg for activity consent status).

Second, tables can be used to confirm which rules apply in different parts of the district/region and for which activities.

Italics are used here to denote terms that would be included in the definitions section of the district plan.

Permitted Activity Rules: Example 1

Permitted activities

12.1.1.1 Permitted Activities

The following activities are permitted in the Residential A zone provided that they comply with the permitted activity requirements, conditions and permissions:

-

- Residential activities;

- Home based businesses;

- Temporary Events.

Permitted activity requirements, conditions and permissions

12.1.1.2 Residential Amenity

-

- The height of any building or structure in the Residential A zone shall not exceed 10 metres.

- The following separation distances shall be provided between buildings and lot boundaries:

- Front boundary: 2.5 metres

- Side boundaries: 1.5 metres

- Rear boundaries: 2.0 metres

- Noise from any activity in the Residential A zone shall not exceed:

- 7am to 7pm Monday to Saturday: 50 dBA (L10)

- 7pm to 10pm Friday and Saturday: 45 dBA (L10)

- All other times: 40 dBA (L10).

- In addition to (b), no single noise event shall exceed 75 dBA (LMax) between the hours of 10pm and 7am.

- Noise shall be measure in accordance with NZS: XXXX.

12.1.1.3: Home-based Businesses

-

- Home-based businesses shall not employ more than two persons (whether resident or not) on any site or in any building on that site.

- No equipment, materials, products, by-products or refuse associated with the home-based business shall be stored outside the building or buildings from which the business operates.

- Etc.,

12.1.1.4: Traffic and Parking

All activities in the Residential A zone shall comply with the traffic management and parking standards contained in rule 9.5.5.3.

Permitted Activity Rules: Example 2

Rural A zone

Permitted Activities

|

Activity |

Requirements, conditions and permissions to be complied with |

Non-compliance |

Applicable objectives and policies |

|

Rule 21.1.2.1 Temporary Events (refer section 10.1 for definition) |

|

Any activity that does not comply with the requirements, conditions and permissions is a restricted discretionary activity (refer rule 21.1.5.1). |

Objective: 9.3 Policies: 9.3.1 9.3.3 9.3.4 |

Controlled Activity Rule: Example 1

Controlled activities

12.1.2.1 Controlled Activities

The following activities are controlled in the Residential A zone provided they comply with requirements, conditions and permissions set out in rule 12.1.2.2 and 12.1.2.3:

-

- Subdivision for the purpose of boundary adjustment;

- Subdivision to create service corridors for network utilities.

Controlled activity requirements, conditions and permissions

12.1.2.2 Boundary Adjustments

-

- The lots affected by the boundary alteration shall continue to comply with the minimum lot sizes for the Residential A zone set out in rule 12.1.1.6; or

- Where the boundary alteration affects lots that are smaller than the minimum permitted size for the Residential A zone, the boundary alteration should not result in any further reduction in lot size; and

- Boundary alternations must not deny access to any lot that has existing access to, or legal frontage to a road.

12.1.2.3 Subdivision for Services

-

- New lots created to provide a corridor for services must not extinguish another existing lot 's legal frontage or access to a road.

- …

Matters of control

12.1.2.4 Matters of Control for Boundary Adjustments:

The matters over which the Whatsup District Council retains control for the purposes of rule 12.1.2.1(a) are:

-

- The size of lots that would exist after a boundary adjustment; and

- Legal and physical access to and from lots affected by the boundary adjustment.

12.1.2.5 Matters of Control for Creation of Service Corridor Lots

The matters over which the council retains control for the purposes of rule 12.1.2.1(b) are: …

Controlled Activity Rule: Example 2

Wharetawhito Heritage Policy Area

(Planning maps B7, C7, and D8)

Controlled Activities

|

Activity |

Requirements, conditions and permissions to be complied with |

Matters over which the council reserves control: |

Applicable objectives and policies |

|

Rule: 7.2.1.1 External minor modifications or alteration to category 2 heritage buildings and structures in the Wharetawhito Heritage Area |

|

|

Objectives: 3.3 3.4 Policies: 3.3.1 3.3.2 3.4.2 3.4.4 |

|

Rule: 7.2.1.2 |

The external minor modifications or alterations of any category heritage building or structure in the Wharetawhito Heritage Policy Area that does not comply with the requirements, conditions and permissions in rule 7.2.1.1 is a discretionary activity. |

||

Restricted Discretionary Activity Rule: Example 1

Restricted Discretionary Activities

12.2.3.1 Restricted Discretionary Activities

The following are restricted discretionary activities in the Residential A zone provided they comply with the requirements, conditions and permissions set out in rule 12.2.3.2.

-

- Activities in the Residential A zones that are not described as controlled, non-complying or prohibited, and that fail to comply with the permitted activity requirements for height and separation distances in rules 12.1.1.2 to 12.1.1.9.

- Home-based businesses employing more than two people at any site or in any building on that site.

- …

Restricted discretionary requirements, conditions and permissions

12.2.3.2 Height and Separation

-

- The maximum height of any building or structure under 12.2.3.1(a) shall not exceed 15 metres.

- The footprint area of encroachment within any of the yards specified 12.2.12(b) shall not exceed more than 5 square metres, and no combination of structures on the site shall have an aggregate length of more than 5 metres along any one boundary.

Matters of discretion

12.2.3.3 Matters of Discretion

The matters over which Council will retain discretion are:

-

- The actual or potential adverse effects created by an increase in height over 10 metres.

- The actual or potential adverse effects created by a reduction in separation distances.

- …

Discretionary Activity Rule: Example 1

Discretionary Activities