The use of structure plans and their content is variable, and readily open to adaptation to meet local issues and circumstances. The following content headings provide a general guide on how a structure plan could be structured and adapted as required to meet its particular objectives and scope:

1. Vision, objectives and development principles

The broad purpose of structure plans can sometimes be lost within the detail of their contents. Placing a vision statement and key objectives at the front can clearly identify the high-level issues being addressed by the structure plan and can focus those involved in implementing the structure plan based on its original intent.

A vision statement is potentially the most aspirational part of the document and inclusive of views derived from the engagement and consultation undertaken. It is a written and visual snap-shot of the qualities the community could look forward to at the end of its nominated timeframe. It is aimed at inspiring and motivating the community - council, developers and end users alike - to achieve the holistic outcome sought through the combination of initiatives presented in the plan. It still needs to be realistic, both within constraints of the area and the resources available.

Key objectives identify specific priorities and strategic areas of focus to help achieve the vision. These could be measurable over time or at least be able to provide a high level of accountability for each decision made.

The principles of good design are important to establish early, as the layout and supporting infrastructure of developments often endure well beyond the life of the built forms that follow. Good design decisions made early, before development is undertaken, can have lasting amenity, function, and cost benefits with relatively modest design input. Design principles should be site specific and help bridge the gap between generic good practice (e.g. the NZ Urban Design Protocol) with those distinctive qualities and constraints of the structure plan area and its context. Furthermore, these principles can be used as a checklist for each structure plan initiative and in the assessment of development proposals that follow.

2. Context and key issues

This section should contain a synopsis of the findings from the research and information analysis undertaken. This is helpful as a way of consolidating the diverse information available, clearly identifying the most relevant aspects and providing an evidence base to back up decisions made during the evolution of the structure plan. Detailed information could be provided in appendices for future reference.

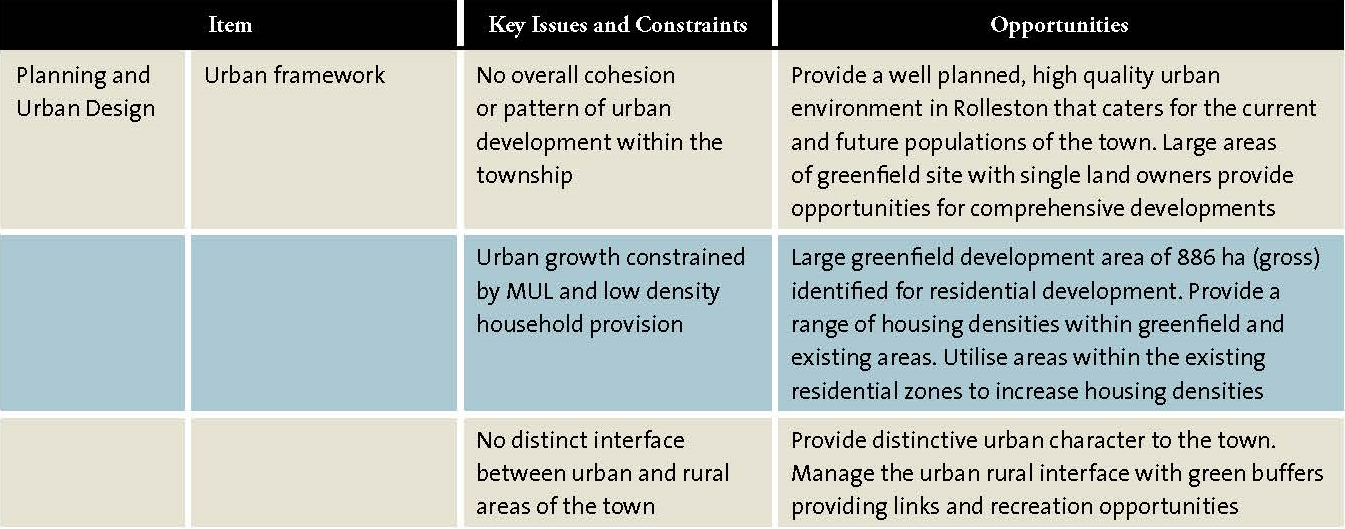

It is recommended that the structure plan includes a summary of the key issues, constraints and opportunities of the existing area, particularly those used to inform the preferred structure plan option and identifying what the subsequent actions should be. This should include consideration of market viability and the feasibility of different development opportunities. An example of key issues, constraints and opportunities from the Rolleston Structure Plan is set out below. :

Table 2. Key Issues, Constraints and Opportunities for Rolleston (Rolleston Structure Plan, 2009)

3. Engagement and consultation summary

Identifying the range of engagement and consultation activities undertaken, who was involved, the level of participation achieved, and the issues identified in the structure plan is a transparent way of demonstrating that the structure plan has taken into account relevant stakeholders, tangata whenua and community views. This is also consistent with the principles for consultation in s82 of the LGA which promote a clear record of how views expressed through consultation have been considered and reflected in the decisions made.

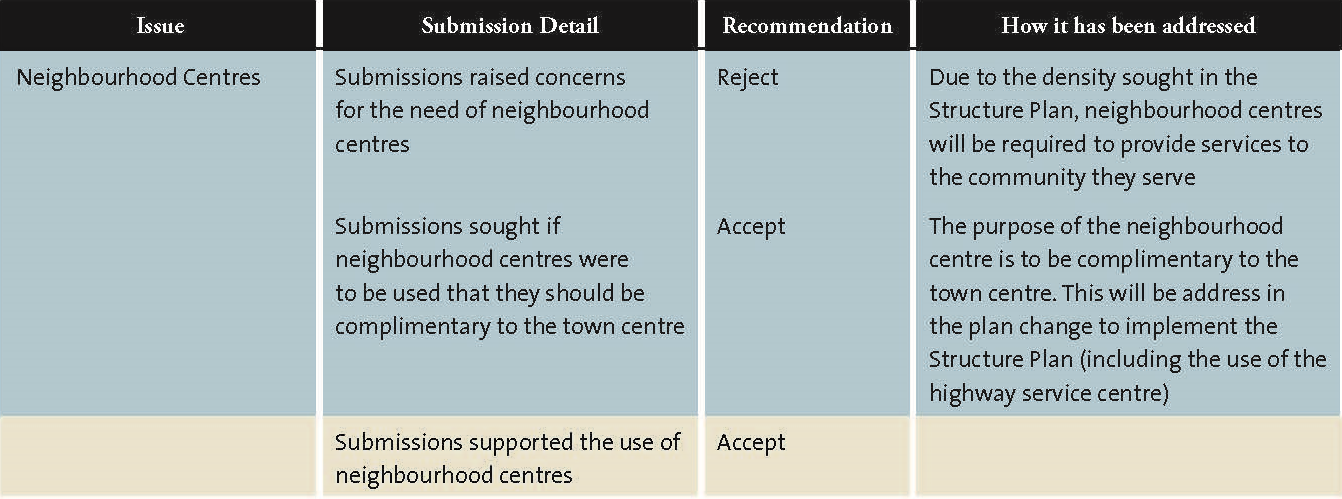

Conflicting views between stakeholders (or with other key issues identified through the analysis process) may be inevitable and in these situations it is useful to provide an appropriate explanation to show how the the issue has been considered, addressed and accepted/rejected. It is important that this is presented systematically to link the issue raised with the response explaining how it has been addressed. A tabular form can be one clear and simple way of communicating this, such as used in the Rolleston Structure Plan below.

Table 3. Summary of submissions and recommendations (Rolleston Structure Plan, 2009).

4. Structure plan overview

This section also provides an opportunity to highlight the overall approach of the structure plan. For example, this may explain what the major drivers for decision-making were in designing the layout and identifying the key aspects, or ‘big moves’, of the structure plan as a whole.

If staging is important for the coordinated implementation of the structure plan layout, it may be necessary to include a summary of these expectations early in the document, rather than in the implementation section at the end.

5. Structure plan components

5.1. Urban form and land use

The rationale for establishing areas of varying urban form should be explained in the structure plan. Urban form is essentially the close link between land uses, including their intensity, and the physical layout of the built environment.

Good urban design practice tends to follow a ‘multi-nodal’ approach, where different urban forms are matched to varying levels of accessibility and connections. For instance, growth of higher density land uses are encouraged to locate around key nodes of higher public transport, cycling and walking accessibility. Alternatively, industrial uses of lower employment densities may be better suited to marginal areas where good links to regional freight routes and supply chains exist. These densities both have recognisable patterns of development and building typologies associated with them. This recognition is important and provides the local community and visitors clear messages over which locations in the built environment have priority or service particular important community and economic functions. Often it will be useful to establish a hierarchy of different urban forms with the structure plan area and communicate this through the structure plan.

There are other potential land use considerations that may need to be explained, including how complementary activities are provided for, how incompatible activities are managed, and how areas of high value or sensitivity (for environmental, cultural or social reasons) will be protected/managed. Demonstrating how demographic change, community needs, and market analysis may influence the quantity, distribution and diversity of particular land uses are further explanations that could be provided.

5.2. Reserves and open space networks

Reserves and open space networks may be used in structure plans as a way of providing for any one of a multiple of the following purposes: the recreational needs of the future population, as a way of managing hazards, the protection of natural or historic heritage, landscape character, amenity, or water quality.

Reserves may be indicated in a variety of ways, such as through notations on the plan or map showing the general area in which a future reserve is proposed but for which the final details are still open to negotiation.

In planning reserves it is good practice to:

- establish a hierarchy and network of open spaces with linkages between them

- provide for both active and passive recreational needs, as well as for heritage protection, stormwater management and off-road linkages within an urban area

- provide flexibility for multiple activities to occur in public spaces (e.g. stormwater reserves for passive open space, adaptable hard courts facilities)

- ensure the amount of reserve land to be set aside is matched to an ability to acquire the land and maintain it. For example: this could be through financial or development contributions or a designation process if in Council ownership, or through a body corporate agreement if in private ownership.

- where reserves acquisition differs from that used in association with more generic subdivision or development provisions, justify that difference in a robust manner (such as through a recreational needs assessment, a water quality study, hazards assessment, or an ecological impact study)

- clearly state in the structure plan when and where the retention of natural features in public and private ownership will be required (such as through rules restricting development potential, or the use of private covenants on private land).

The needs assessment should relate to the council's policy or position on the level of service for active and passive reserves relative to the population size and character. This is usually expressed in terms of the range of reserve types that may be applicable to the local conditions.

5.3. Community facilities

The nature and scale of the community infrastructure provided for in a structure plan area will be dependent on the type of development being contemplated. A needs assessment may be required as part of the structure plan process to inform, supplement or evaluate stakeholder aspirations and community facility needs. The needs assessment could determine if specific facilities should be provided based on criteria such as future population growth and demographics, the needs of the population, and the extent to which current facilities can meet those needs.

In an urban situation, consultation should be undertaken with social service provided to determine what facilities are needed or planned. For example, consultation should be undertaken with schools and the Ministry of Education may be needed to determine whether additional schools are needed or planned, if there is capacity in existing schools, or if the structure plan may adversely affect a school's catchment through changing land uses. Other parties who may have an interest in how the structure plan could impact on the way they provide community services include social service providers, health providers and emergency service providers and these parties should also be consulted as appropriate to determine the current and future community facility priorities.

5.4. Transport and movement

A good understanding of transport patterns and behaviours in both rural and urban settings is important to achieve good integration between land-use and transport outcomes. A robust assessment of transport patterns and future needs is a key part of the structure plan process and this can help to:

- provide for a choice of transport routes and modes (bus, walking or bicycle, for example), access to them and routes and modes appropriate to the level and type of development anticipated

- match the transport network density to development intensity (higher urban density may require smaller block sizes and a multimodal transport network with more connections)

- promote the safe and efficient movement of people and vehicles while successfully resolving tensions between the needs and objectives of pedestrians, public transport users and motorists.

Implementing structure plans through RMA plans can present a challenge because the preferences of developers, unforeseen site constraints or some engineering requirements may mean development takes on a different form to that envisaged by the structure plan. It is therefore important to set minimum standards to ensure that the capacity of infrastructure provided matches the likely level of development.

Where structure plans are implemented through RMA plans, transport provisions should be prepared in such a way as to provide certainty over the general routes that are to be followed to link proposed land uses, but retain enough discretion to allow flexibility in the final design and layout of the links.

Some RMA plans get around the problem of not knowing the precise alignment of infrastructure such as roads by providing indicative roading layouts and transport links on structure plans. These then form a matter of over which a council may retain control when subdivision consent is applied for. This can provide an element of design flexibility to meet both the objectives of the council and the developer.

To address the effects of traffic, the early and ongoing involvement of transport planners and engineers (including those from The New Zealand Transport Agency, where appropriate) is important to provide sound analysis and advice.

5.5 Natural hazards

Natural hazards are one of the key assessments required when undertaking structure planning. A good understanding of natural hazards and associated risk to development is important for ensuring that the capacity of an area can be understood with certainty and planned for accordingly. Natural hazard assessment will assist in determining the suitability of land for future use and development of infrastructure. Natural hazard assessments may identify areas that should be avoided altogether or where specific hazard risks need to be addressed before development could occur.

Assessment of flood risk and the management of stormwater within some catchments may have a significant influence on urban form and development. In such areas stormwater catchment management will often be a key component of the structure plan. For example, assessment of flood risk may lead to minimum requirements for building platform heights, the need for land to be set aside for stormwater storage to mitigate peak flow, and the need for overland flow paths for events that exceed design parameters. Stormwater treatment requirements may also lead to requirements for low impact urban design in new development and the use of green infrastructure.

Where hazard assessment is undertaken in detail at the time of structure planning, there is then the potential to look toward multiple uses of land set aside for hazard mitigation. In many cases this land can also be used for open space and other low intensity, short duration or less sensitive activities (e.g. car parking, ecological enhancement, etc).

For low probability and high consequence hazard events such as tsunami, structure planning enables consideration to be given to the level of risk acceptability, and also consideration of feasibility for escape routes to high ground. Risk acceptability refers to the level of risk that can be accommodated when planning for a development and it is important that this is clearly defined. This is important to provide certainty to developers, communities, council about what this level of acceptable risk is and who the risk needs to be acceptable to.

Levels of risk acceptance should be defined based on standards found in planning documents or best practice guidelines for specific types of hazard (e.g. Preparing for future flooding; Preparing for coastal change, Tools for Estimating the Effects of Climate Change on Flood Flow, etc). Common factors affecting the acceptability of risk include control of the risk (degree to which person can modify risk), fairness (whether everyone is affected equally), familiarity (common versus new unfamiliar risks) and voluntariness (extent to which risk is accepted versus imposed). For greenfield areas, acceptable risks to life and property are generally very low. In areas of redevelopment higher risks may be tolerated, but steps should always be taken to reduce the risk from natural hazards where practicable. For more information on a risk based management approach to natural hazards, refer to the Natural Hazards guidance note.

5.6. Infrastructure networks

The ability to extend network infrastructure such as roads, water, gas, electricity and telecommunication facilities can significantly affect the availability and viability of land-use options for the area being structure planned. Network utility providers can therefore hold considerable influence in the successful implementation of a structure plan.

Where structure plans are to be implemented via a RMA plan, early canvassing of possible structure plan provisions which meet both the objectives of the council and the network utility provider can help provide certainty in the development of the structure plan, and avoid delays in its implementation. Generic roading designs that include the provision for infrastructure (e.g. wide road berms) can be beneficial to reassure infrastructure providers that there is an ability to service the development.

6. Implementation plan

The success of a structure plan is often determined on how straightforward and practical it is to deliver it on the ground. Numerous development initiatives will have been identified throughout the structure plan document and the implementation section should aim to collate those initiatives and identify the appropriate methods, timescales and responsibilities to implement them.

There are several methods or approaches available to implement a structure plan and it is likely that a combination of these will need to be utilised, including:

- Statutory planning, including RMA plan mechanisms

- Investment in land, infrastructure and council owned facilities and services, to facilitate, enable and support growth

- Participation in the ‘market’, either directly or in association with the private sector, for example in a possible ‘demonstration project’ using council owned land

- Other direct actions by council, such as investigating proposals, developing guidelines and standards, operational policies, etc.

- Indirect actions by council, such as coordinating, liaising, encouraging, promoting or facilitating action by others

- Requiring action by others, such as developer provided infrastructure.

With a complex matrix of initiatives and methods of implementation, it is critical that the structure plan sets out the necessary actions that will coordinate and support the ongoing implementation of the structure plan and integrated growth in general.

An action plan is useful to systematically set out relevant considerations, such as the topic area, required action, land requirements, timeframes/priority, cost implications, methods and responsibility.

A good example of an implementation action plan from the Rolleston Structure Plan is set out below. This identified specific actions associated with the structure plan the timeframes and cost implications to achieve and the methods to achieve it. This can provide an effective method to provide certainty to all parties about who is responsible for what and when to help ensure the structure plan outcomes are successfully implemented. For more information on the Rolleston Structure Plan process, refer to the Rolleston Structure Plan case study.

Table 4. Movement Network Action Plan (Rolleston Structure Plan, 2009).

A staging plan should be included to ensure a coordinated approach is taken to achieve the holistic outcomes desired within the structure plan. It is an early signal to those responsible for implementation at the appropriate timeframes to start planning and allocating funding and resources as necessary to achieve particular parts of the structure plan. It is also a way of managing landowner and developer expectations. Deliberate mechanisms will also need to be put in place for later stages to prevent interim initiatives, such as further subdivision, causing significant difficulties in managing and delivering the structure plan outcomes.

7. Monitoring and review

Structure plans should be regarded as ‘living’ documents, as circumstances influencing development change and new development can influence and shape subsequent development. Issues or opportunities often arise during the implementation of the plan that were not anticipated when the structure plan was prepared and some flexibility is necessary to resolve emerging issues (e.g. funding and infrastructure changes), integrate potential improvements or adapt to changes in good practice. Also refer to the monitoring and review process.

This section should outline regular review periods, appropriate performance criteria to assess successful progress and mechanisms that ensure the structure plan remains relevant for the community. Such mechanisms could include the establishment of an ongoing liaison group including community and stakeholder representatives.